Lecture 08

2022-10-19 | Week 4 | by Siddarth Krishnamoorthy

Hi! Siddarth here. This lecture note covers slides 41 to 78 of data palooza.

Table of Contents

Typing continued

Gradual typing

In Lecture 7, we have seen both static and dynamic typing. There’s actually a less well-known hybrid approach called gradual typing. It’s used by a few well known languages like PHP and TypeScript, so it merits discussion. In gradual typing, some variables may have explicitly annotated types, while others may not. This allows the type checker to partially verify type safety prior to execution, and perform the rest of the checks during run time.

With gradual typing, you can choose whether to specify a type for variables/parameters. If a variable is untyped, then type errors for that variable are detected at run time. But if a variable is typed, then it’s possible to detect some type errors at compile time. But what if we pass an untyped variable as an argument to a typed variable? Look at the following code snipped for a concrete example.

def square(x: int):

return x * x

def what_happens(y):

print(square(y))

This is actually allowed in gradually typed languages! If you pass an untyped variable as an argument to what_happens, the type checker will check for errors during run time. This way, if you do use an invalid type, the program will generate an error the moment an incompatible type is detected.

Let’s try and classify a language.

fun greet(name: String) {

print("Hello, $name!")

}

fun main() {

var n = "Graciela";

greet(n);

n = 10;

}

Is this language dynamically, statically or gradually typed, given that the code generates the following error?

The integer literal does not conform to the expected type String

Answer: Even though it doesn’t look like it at first glance, the language is statically typed, since you can’t assign n to a value of a new type. This means that n has a fixed type, and that the language is using type inference. This language is actually Kotlin.

Strong typing

Now that we have a good idea of static and dynamic typing, we’re going to look at the various type checking approaches on the basis of strictness. A strongly typed language ensures that we will never have undefined behaviour at run time due to type issues. This means that in a strongly typed language, there is no possibility of an unchecked run time type error.

These are the minimum requirements for a language to be strongly typed:

- The language is type safe: This means that the language will prevent an operation on a variable

xifxs type doesn’t support that operation.int x; Dog d; a = 5 * d; // Prevented - The language is memory safe: This means that the language prevents inappropriate memory accesses (e.g., out-of-bounds array accesses, accessing a dangling pointer)

int arr[5], *ptr; cout << arr[10]; // Prevented cout << *ptr; // PreventedThese can be enforced either statically or dynamically.

Languages usually use a few techniques to implement strong typing:

- Before an expression is evaluated, the compiler/interpreter validates that all of the operands used in the expression have compatible types.

- All conversions between different types are checked and if the types are incompatible (e.g., converting an int to a Dog), then an exception will be generated.

- Pointers are either set to null or assigned to point at a valid object at creation.

- Accesses to arrays are bounds checked; pointer arithmetic is bounds-checked.

- The language ensures objects can’t be used after they are destroyed.

In general, strongly typed languages prevent operations on incompatible types or invalid memory.

Why do we need memory safety?

Why do strongly typed langauges require memory safety? To answer this question, consider the following example in C++ (a weakly typed language).

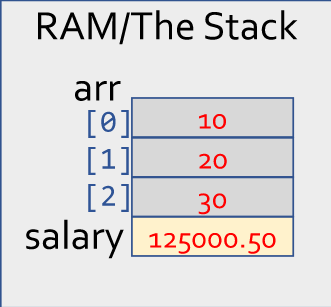

// C++

int arr[3] = {10, 20, 30};

float salary = 120000.50;

cout << arr[3]; // out-of-bounds access

arr[3] actually access the value stored in salary, since all local variables are stored on the stack. So if a language is not memory safe, then it’s possible to access a value (like salary) using an invalid type (int instead of float). Accessing a dangling pointer is another example of how memory safety can violate type safety.

|

|---|

In C++, arr[3] would actually access the value stored in salary as if it were an integer! |

// Accessing a dangling pointer

float *ptr = new float[100];

delete [] ptr;

cout << *ptr; // is this still a float?

Checked type casts

A checked cast is a type cast that results in an exception/error if the conversion is illegal. Let’s look at a concrete example in Java, a strongly typed language. Consider the following snippet of code.

public void petAnimal(Animal a) {

a.pet(); // Pet the animal

Dog d = (Dog)a; // Probably a dog, right?

d.wagTail(); // It'll wag its tail!

}

...

public void takeCareOfCats() {

Cat c = new Cat("Meowmer");

petAnimal(c);

}

In this case, the program would output a type error saying that Cat can’t be type cast to Dog.

java.lang.ClassCastException: class Cat cannot be cast to class Dog

A similar snippet of code in C++ however would run, even though we are dealing with an object of type Cat, not Dog!

void petAnimal(Animal *a) {

a->pet(); // Pet the animal

Dog* d = (Dog *)a;

d->wagTail();

}

...

void takeCareOfCats() {

Cat c("Meowmer");

petAnimal(&c);

}

When the C++ program actually executes d->wagTail(), anything could happen. This is undefined behaviour (we will cover undefined behaviour later in this lecture).

Why should we prefer strongly typed languages? Well, they have two main benefits.

- They dramatically reduce software vulnerabilities (e.g. buffer overflows).

- They allow for early detection and fixing of errors/bugs.

The definition of strong typing is disputed. Many academics argue for a stronger definition (e.g. all conversions between types should be explicit, the language should have explicit type annotations for all variables, etc.). But ultimately while these definitions may make a languages type system stricter, they don’t impact the languages type or memory safety.

Weak typing

Weak typing is essentially the opposite of strong typing, in that it does not guarantee that all operations are invoked on objects/values of the appropriate type. Weakly typed languages are generally neither type safe nor memory safe.

Undefined behaviour

In a strongly typed language, we know that all operations on variables will either succeed or generate an explicit type exception at runtime (in dynamically-typed languages). But in weakly-typed languages, we can have undefined behavior at runtime! Undefined behaviour is the result of executing a program whose behaviour is prescribed as unpredictable in the language spec. Consider the following example in C++.

// C++ example w/undefined behavior!

class Nerd {

public:

Nerd(string name, int IQ) { ...}

int get_iq() { return iq_; }

...

};

int main() {

int a = 10;

Nerd *n = reinterpret_cast<Nerd *>(&a); // reinterpret the integer as a Nerd object

cout << n->get_iq(); // ?? What happens?!?!?

}

When we call the get_iq method on n (which is actually an integer), the program is going to crash!

It’s tough to say whether or not a language is weakly or strongly typed just from looking at it’s behaviour in one situation. Consider the following example from a mystery language.

# Defines a function called ComputeSum

# In this language, @_ is an array that holds

# all arguments passed to the function

sub ComputeSum {

$sum = 0;

foreach $item (@_) { # loop thru args

$sum += $item;

}

print("Sum of inputs: $sum\n")

}

# Function call

ComputeSum(10, "90", "cat");

This outputs

Sum of inputs: 100

This may seem like the mystery language is weakly typed, but in fact the mystery language is Perl, which is strongly typed! Weak typing is the situation where an undefined result occurs because we apply some operation to a type that does not support it. In Perl, the + operator does support the string type. It will convert the string to an integer, if possible (e.g., if it holds all digits). If not, it’ll convert the string to a value of zero. Then it’ll perform the add. So while Perl does perform implicit conversions which might not do what you want, its behavior is never undefined.

Type casting, conversion and coercion

Type casting, conversion and corecion are different ways of explicitly or implicitly changing a value of one data type into another. For example, we can change the type of a variable using static_cast.

void convert() {

float pi = 3.141;

cout << static_cast<int>(pi);

}

Often the types you are converting will be related to each other, for instance like float and double. Both types hold real-valued numbers, but double can hold a much wider range of values and have a higher precision relative to float (at the cost of more memory). So in language theory, we say that float is a subtype of double, or alternatively that double is a super type of float.

More formally, given two types $T_{sub}$ and $T_{super}$, we say that $T_{sub}$ is a subtype of $T_{super}$ if and only if

- an object of type $T_{sub}$ can be used anywhere that code expects an object of type $T_{super}$.

- every element belonging to the set of values of type $T_{sub}$ is also a member of the set of values of $T_{super}$.

Does this mean int is a subtype of long in C++? Yes! Since all operations that can be performed on a long can also be performed on an int (+, -, *, /, etc.) and every int value is also in the set of long values.

What about this example?

class Person { ... };

class Nerd: public Person { ... };

Is Nerd a subtype of Person? Yes, since all operations that can be performed on a Person can also be performed on a Nerd and all Nerds belong to the set of Persons. For a more tricky example, is int a subtype of const int? Yes, because all operations that can be performed on a const int can also be performed on an int and int and const int have the same set of values.

There are two ways of converting between types - conversions and casts

Type conversions

If we generate a whole new value of the new type, we say that we are performing a type conversion. The new value would occupy a different storage location and have a different bit representation.

void convert() {

float pi = 3.141;

cout << (int)pi; // 3

}

This is a conversion since the compiler generates a new temporary value of a different type.

Type casts

If to convert a value’s type, we just reinterpret the bits of the original value in a manner consistent with the new type, we say we are performing a type cast. In type casts, no new value is created.

class Person { ... };

class Nerd : public Person { ... };

void cast() {

Nerd n("Steph",110);

Person &p = n;

cout << "Hi " << p.getName();

}

In the above example, p refers to the original Nerd object, but interprets the bits as if it were a Person.

Conversions and casts can be widening or narrowing.

- Widening means the target type is a super type, and can fully represent the source type’s values.

- Narrowing means the target type may lose precision or otherwise fail to represent the source type’s values. The target type could be a subtype (like

longandshort), or the two types could also have a non-overlapping set of values (likeunsigned intandint).

Conversions and casts can also be expliict or implicit.

- An explicit conversion requires the programmer to use explicit syntax to force the conversion/cast

- An implicit conversion (also called coercion) is one which happens without explicit conversion syntax.

An implicit conversion or cast that is widening is called a type promotion.

Explicit conversions and casts

When you’re using an explicit conversion or cast, you’re telling the compiler to change what would be a compile time error to a run time check.

class Example

{

public void askToCookFavoriteMeal(Machine m) {

if (m.canCook() && m.canTalk()) {

RobotChef r = m; // Line 5

r.requestMeal("seared ahi tuna");

}

}

}

For example, at line 5, the programmer may know that converting from Machine to RobotChef is always safe, but a statically typed compiler can’t know that. Therefore, the compiler will output an error. With an explicit cast (like in the example below), the compiler knows that the programmer wants to do this, and allows the code to compile.

class Example

{

public void askToCookFavoriteMeal(Machine m) {

if (m.canCook() && m.canTalk()) {

RobotChef r = (RobotChef)m; // Line 5

r.requestMeal("seared ahi tuna");

}

}

}

If the language is strongly typed, then it will perform a runtime check to ensure the type conversion is valid. In weakly typed languages, however, improper casts/conversions are often not checked at run time, leading to nasty bugs!

Here are a few examples of explicit type conversions in different languages.

- C++

// Explicit C++ conversions float fpi = 3.14; int ipi = (int)fpi; // old way int ipi2 = static_cast<int>(fpi); // new way RobotCook *r = dynamic_cast<RobotCook *>(m);

Ironically, even though static_cast<int>(fpi) is creating a new value (so it’s performing a conversion), C++ calls it a cast

- Python

# Explicit Python conversions fpi = 3.14 ipi = int(pi) - Haskell

-- Explicit Haskell conversion fpi = 3.14 :: Double ipi = floor(foo) -- converts to 'Integral' super type - JavaScript

-- Explicit JavaScript conversion fpi = 3.14 ipi = parseInt(pi) -- converts to int

Boxing and unboxing

A boxing conversion converts a primitive type into an object that holds only the primitive value as its member. Similarly, an unboxing conversion converts a boxed object back to a primitive value. Let’s see an example from Java.

// Java - Explicit conversion of i to a boxed Integer

int i = 10; // i is a primitive, stored on the stack

Integer boxed_i = new Integer(i); // boxed_i holds 10

// Explicit unboxing of the Integer to get its value

int unboxed_i = boxed_i.intValue();

Integer is Java’s inbuilt boxed type. boxed_i is an Integer object with a single member, the int value. Calling boxed_i.intValue() returns the primitive int value.

Boxed primitives are used to store primitive values in Java containers (e.g., ArrayList) because its containers don’t support unboxed primitives.

Implicit conversions and casts

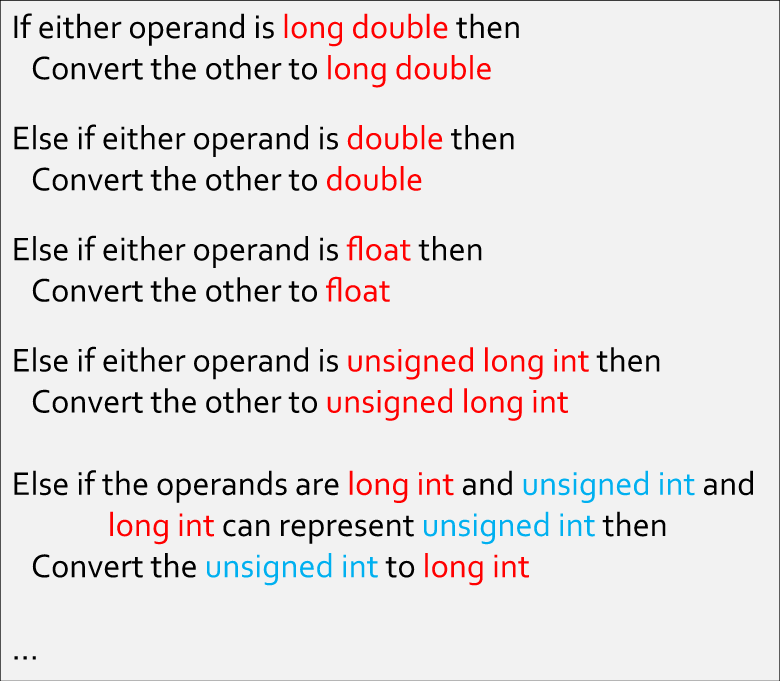

Most languages have a set of rules that govern implicit conversions that may occur without warnings/errors. For instance, here are some associated with C/C++ for coercion during binary operations (e.g., X + Y). When learning a new language, it helps to understand its implicit conversion policy!

|

|---|

| Type casting rules in C++ |

Let’s look at some examples of implicit conversions and casts in different languages.

- C++

// Implicit C++ conversions

void foo(double x) { ... }

int main() {

bool b = true;

int i = b; // b promoted to int

double d =

3.14 + i; // i promoted to double

i = 2.718; // 2.718 coerced/narrowed to int

foo(i); // i promoted to double

}

When we promote i to double in the statement double d = 3.14 + i;, it brings the all of the operands to a common super type so that addition can be performed. In such an expression with mixed types, the types of all variables must have “type compatibility” with each other.

In the above example, i is still an int, and it’s value is 2, not 2.718. Compilers (especially recent ones) will often generate warnings for narrowing coercions which may not preserve the full source value.

- Python

# Implicit Python conversions

i = 123 + True # True promoted to int (124)

f = 1.23

sum = i + f # i promoted to float

- JavaScript

// Implicit JavaScript conversion

str = "sk" + 8 // coercion of 8 to string

n = "10" * "15" // coercion to numbers

- Java

// Implicit (un)boxing in Java

int i = 10;

// implicit boxing

Integer boxed_i = i;

// implicit unboxing

int unboxed_i = boxed_i;

Haskell doesn’t do implicit type conversions.

Type casting in depth

Casting is when we reinterpret the bits of the original value in a manner consistent with a different type. No new value is created by a cast, we just interpret the bits differently. The most common type of casting is from a super type to a subtype, for example, when upcasting from a subclass to a super class to implement polymorphism. Downcasting is another example, where we go from a super class to a subclass.

// C++

class Mammal { ... }

class Person : public Mammal { ... };

class Nerd: public Person { ... };

void ask_hobbies(Person &p) { ... }

void date_with_nerd(Nerd &n) {

ask_hobbies(n); // upcast Nerd to Person

}

void date_with_mammal(Mammal &m) {

// downcast Mammal to Person

Person& p = dynamic_cast<Person &>(m);

ask_hobbies(p);

}

Here is an example of implicit casting.

// C++

void print(unsigned int &val)

{ cout << val << endl; }

int main() {

int j = -42;

print(j); // prints 4294967254

}

This cast simply reinterprets the value stored by j as if it were an unsigned int.

Many compilers will not warn about implicit casts when they are between unsigned and signed types - even though they are narrowing.

// C++

void print(const string &s)

{ cout << s << endl; }

int main() {

string s = "UCLA";

print(s);

}

This cast implicitly converts from type string to const string.

We can also use casting to change the interpretation of pointers and read/write memory using a different type. For example, consider the following snippet of code in C++.

void cast() {

int a = 1078530000;

int *ptr = &a;

// Treat ptr as a float *

cout << *reinterpret_cast<float *>(ptr); // prints 3.14159

}

The code treats ptr as if it is a pointer to a float (using reinterpret_cast), and when we dereference ptr, the bits are interpreted as if they were a float.

We can also reinterpret the value of an integer as a pointer (though this isn’t recommended).

void cast() {

int a = 12340;

// Treat a as a double pointer

// Store value of pi at address 12340!

*reinterpret_cast<double *>(a) = 3.14159;

}

So what’s better, explicit or implicit type conversions? It depends! Explicit type conversions lead to more verbose code and is less convenient, but reduces the likelihood of bugs. Implicit type conversions makes code less verbose and is more convenient, but greatly increases the likelihood of bugs.

Here are a few final examples of casting and conversions.

$a = 5;

if ($a) {

print("5 is true!");

}

From this snippet of code, we can infer that the language supports type coercion, since it does a narrowing coercion from an integer value 5 to a boolean value false.

The language is actually Perl.

In the following example, we are told that the program doesn’t work if we remove the float32 conversion.

func main() {

var x int = 5

var y float32 = 10.0

var result float32

result = float32(x) * y // doesn't work if we remove float32()

fmt.Printf("5 * 10.0 = %f\n", result)

}

From this, we can infer that the language requires explicit conversions between even comparable types (like int and float).

The language is actually Golang.