Lecture 07

2022-10-17 | Week 4 | by Siddarth Krishnamoorthy

Hi! Siddarth here. This lecture note covers the first 41 slides of data palooza.

Table of Contents

Data Palooza

In the next few lectures, we will be covering the internals of how many languages manage data (including types, variables and values). We won’t be covering specific languages, but will instead look at patterns that occur across many languages. Before that, let’s do a brief introduction of some of the terms we will be discussing.

Variables and Values

A variable is the symbolic name associated with a location that contains a value or a pointer. A value is a piece of data with a type (usually) that is either referred to by a variable, or computed by a program. For a concrete example, consider the statement

a = 42

Here a is a variable, and 42 is a value.

What are the facets that make up a variable?

- names: variables almost always have a name

- types: a variable may (or may not) have a type associated with it

- values: a variable stores a value (and its type)

- binding: how a variable is connected to its current value

- storage: the slot of memory that stores the value associated with the variable

- lifetime: the timeframe over which a variable exists

- scope: when/where a variable is accessible by code

- mutability: can a variable’s value be changed?

What are the facets that make up a value?

names: variables almost always have a name- types: a value will always have a type associated with it

values: a variable stores a value (and its type)binding: how a variable is connected to its current value- storage: the slot of memory that stores the value

- lifetime: the timeframe over which a value exists

scope: when/where a variable is accessible by code- mutability: can a value be changed?

Lifetime and scope seem similar, but they are not the same. Lifetime refers to the existence of the variable, whereas scope refers to the accessibility of a variable. It is entirely possible for a variable to be out-of-scope but still be alive.

Variable names

What must a language designer consider when deciding variable naming rules for a language? There are multiple possible choices here, and there isn’t one single correct answer.

- Almost all languages stipulate that names should contain valid characters

- Almost all languages stipulate that names should not be the same as keywords or constants

- Most languages have a rule that disallows spaces in variable names

- Some languages have rules about special characters in names, some enforce length restrictions, and some even enforce some sort of case sensitivity rule.

Practically, variable naming conventions are more important than the naming rules of languages. These conventions are usually designed to enforce some degree of standardisation across a codebase. A good example of a standard would be Google’s standard.

Why do most loops idiomatically use i or j for loop variables? It all goes back to Fortran, the first standardised programming langauge. Fortran had a quirky rule where if you didn’t explicitly declare a variable type, it would the first letter of the name to determine the type. Variables starting from a-h and o-z defaulted to floats, while variables starting from i-n defaulted to integers.

Variable storage

Variables and values are stored in one of three different places: the stack, the heap or the static data area.

|

|---|

| Layout of program memory. Function parameters and local variables are stored on the stack. Variables dynamically allocated during runtime lie in the heap. Static members and globals are stored in the static data area. |

Usually local variables and function parameters are stored on the stack. Dynamically allocated objects and values are usually stored on the heap. Most languages store global and static variables in the static data area. Of course, you can also have combinations of these; for example, a pointer that is stored on the stack, but whose value lies on the heap.

Variable types

What can you infer about a value, given its type?

- The set of legal values it can hold

- The operations we can perform on it

- How much memory you need

- How to interpret the bytes stored in RAM

- How values are converted between types

Variable lifetime and scope

Every variable and value has a lifetime, over which they are valid and may be accessed. Note that it is possible for a variable to be “alive” during execution, and yet not be accessible. Some languages give the programmer explicit control over the lifetime of a value, while others completely abstract this away.

void bar() {

...

}

int main() {

int x = 5;

bar();

...

}

A variable is in scope if it can be explicitly accessed by name in that region.

void bar(int *ptr) {

cout << x; // ERROR! x isn’t in-scope here!

cout << *ptr; // Even though its value can be accessed

}

void foo() {

int x;

cout << x; // x is in-scope here

bar(&x);

}

There are two primary approaches to scoping: lexical (or static) scoping and dynamic scoping. We will cover these topics in the next lecture.

Variable binding

As we have seen in Lecture 1, different languages have different ways of binding variable names with values. For example a C++ variable name directly refers to the storage location holding it’s value, while in Python, a variable holds an “object reference”, which then in turn points to the actual value. We will cover the major binding approaches in detail later on.

Mutability

If a variable is immutable, then it’s value cannot be changed once assigned, and vice versa if a variable is mutable. Most languages have some form of immutability. In C++, variables can be made immutable using the const keyword. In Haskell, all variables are by default immutable. Immutability might seem like it makes the language less flexible (and it does to some extent), it also allows for the program to be less buggy, and can also allow for some compiler optimisations to take place.

Types

In this section, we will take a deep dive into typing and type checking. You should hopefully get a much better idea of the implications of a type system.

Before proceeding, it’s worth asking if are types even necessary to create a programming language? Yes! It is possible to have a language with no types. Assembly languages are one such example of languages with no type system. They just have a register that holds a 32 (or 64) bit value. The value could represent anything (an integer, float, pointer, etc.). BLISS is another example of a language with no types.

MODULE E1 (MAIN = CTRL) =

BEGIN

FORWARD ROUTINE

CTRL,

STEP;

ROUTINE CTRL =

BEGIN

EXTERNAL ROUTINE

GETNUM, ! Input a number from terminal

PUTNUM; ! Output a number to terminal

LOCAL

X, ! Storage for input value

Y; ! Storage for output value

GETNUM(X);

Y = STEP(.X);

PUTNUM(.Y)

END;

ROUTINE STEP(A) =

(.A+1);

END

ELUDOM

But virtually all modern languages have a type system, since it makes programming so much easier and safer.

Must every variable have a type in a typed language? No! In Python for example, variables are not associated with types.

# Python

def foo(q):

if q:

x = "What's my type?" # string

...

x = 10 # int

In general, many dynamically typed (don’t worry, we will cover them in this lecture) languages don’t associate variables with types. However, note that a value is always associated with a type.

Types can broadly be classified into two categories, primitive and composite. Primitive data types are a set of types from which other types are constructed. Composite data types are those types which can be constructed using primitive and composite data types.

Examples of primitive data types:

- Integers

- Booleans

- Characters

- Enumerated types (Enums)

- Floats

- Pointers

Examples of derived data types:

- Arrays

- Structs

- Variants/Unions

- Objects

- Tuples

- Containers

There can also be data types that don’t fall into either category.

- Functions

- Generic types

- Boxed types

A boxed type is just an object whose only data member is a primitive (like an int or a float)

class Integer {

public:

int get() const { return val_; }

private:

int val_;

};

Type checking

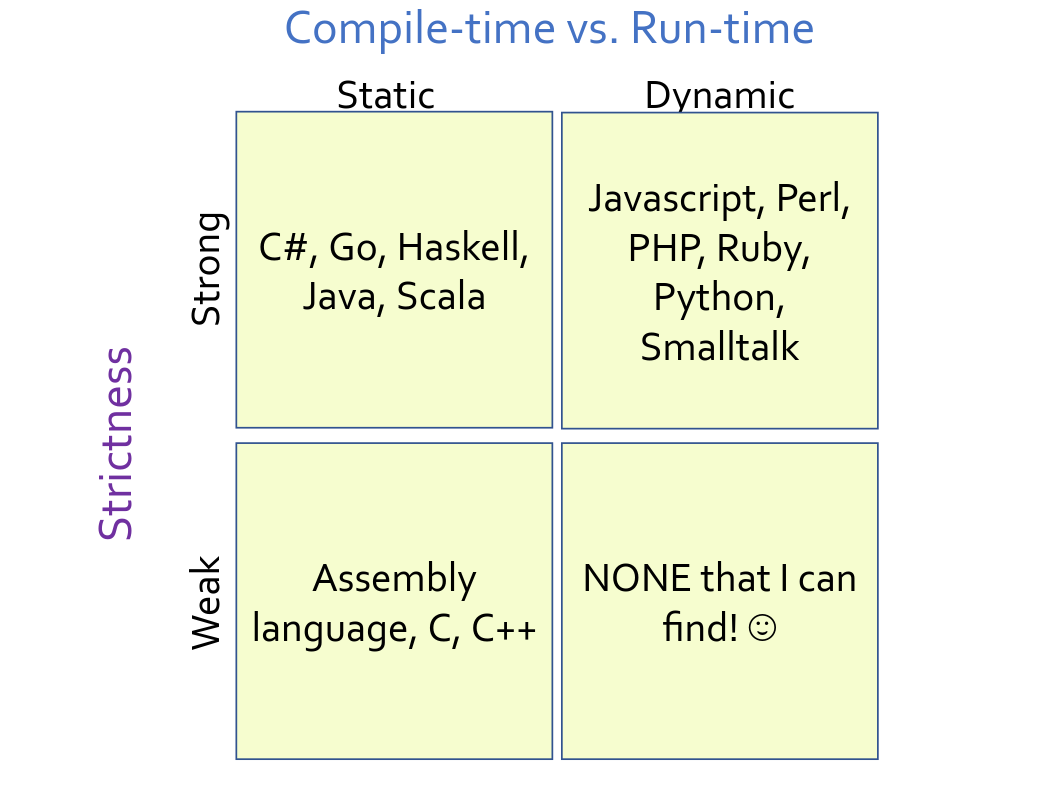

Type checking is the process of verifying and enforcing constriants on types. Type checking can occur during compile time (static) or during run time (dynamic). The language can also specify the degree of strictness for type checking (strong and weak type checking). We will go into more detail on all of these topics.

|

|---|

| Type checking approaches. Type checkers can be classified on the basis of whether they run during compile time or during run time. Type checkers can also be classified on the basis of strictness (strong or weak). |

Static typing

Static typing is the process of verifying that all operations in a program are consistent with the types of the operands prior to program execution. Types can either be explicitly specified (like in C++) or can be inferred from code (like in Haskell). For inferred types, if the type checker cannot assign distinct types to all variables, functions, and expressions or cannot verify type safety, then it generates an error. But if a program type checks, then it means the code is (largely) type safe, and few if any run time checks need to be performed.

To support static typing, a language must have a fixed type bound to each variable at the time of definition.

Type Inference

Type inference refers to the automatic detection of types of expressions or variables in a language. Consider the following example:

void foo(_____ x, _____ y) {

cout << x + 10;

cout << y + " is a string!";

}

What would be the types of x and y? int and string, right! The compiler can infer that y is an string from the fact that we perform the operation y + " is a string", which is only valid if y is a string. What about x? It seems like x can only be an int. But consider this example:

void foo(_____ x, _____ y) {

cout << x + 10;

cout << y + " is a string!";

}

void bar() {

double d = 3.14;

foo(d,"barf");

}

Here, it makes more sense for x to be a double. So type inference is actually a complex constraint satisfaction problem.

Many statically typed languages now offer some form of type inference. C++ has the auto keyword

// C++ type inference with auto

int main() {

auto x = 3.14159; // x is of type int

vector<int> v;

...

for (auto item: v) { // item is of type int

cout << item << endl;

}

auto it = v.begin(); // it is of type vector<int>::iterator

while(it != v.end()) {

cout << *it << endl;

++it;

}

}

Go similarly infers the type of variables from the right-hand-side expression

// GoLang type inference

func main() {

msg := "I like languages"; // string

n := 5 // int

for i := n; i > 0; i-- {

fmt.Println(msg);

}

}

Conservatism

Static type checking is inherently conservative. This means that the static type checker will disallow perfectly valid programs that never violate typing rules.

This is due to the fact that for Turing-complete languages, it is not possible to have a sound (meaning all incorrect programs are rejected), decidable (meaning that it is possible to write an algorithm that determines whether a program is well-typed), and complete (meaning no correct programs are rejected) type system. This follows from Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. (Don’t worry if you don’t understand this, it won’t be on the exam :))

For an example, consider the following program:

class Mammal {

public:

virtual void makeNoise() { cout << "Breathe\n"; }

};

class Dog: public Mammal {

public:

void makeNoise() override { cout << "Ruff\n"; }

void bite() { cout << "Chomp\n"; }

};

class Cat: public Mammal {

public:

void makeNoise() override { cout << "Meow!\n"; }

void scratch() { cout << "Scrape!\n"; }

};

void handlePet(Mammal& m, bool bite, bool scratch) {

m.makeNoise();

if (bite)

m.bite();

if (scratch)

m.scratch();

}

int main() {

Dog spot;

Cat meowmer;

handlePet(spot, true, false);

handlePet(meowmer, false, true);

}

The compiler generates an error during the compilation of this code

error: no member named 'scratch' in 'Mammal'

even though the code only asks Dogs to bite and Cats to scratch.

Pros of static type checking

- Produces faster code (since we don’t have to type check during run time)

- Allows for earlier bug detection (at compile time)

- No need to write custom type checks

Cons of static type checking

- Static typing is conservative and may error our perfectly valid code

- It requires a type checking phase before execution, which can be slow

Dynamic typing

Dynamic type checking is the process of verifying the type safety of a program at run time. If the code is attempting an illegal operation on a variable’s value, an exception is generated and the program crashes. Here are some examples of dynamic type checking at run time.

def add(x,y):

print(x + y)

def foo():

a = 10

b = "cooties"

add(a,b)

outputs

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

def do_something(x):

x.quack()

def main():

a = Lion("Leo")

do_something(a)

outputs

AttributeError: 'Lion' object has no attribute 'quack'

Most dynamically typed languages don’t require explicit type annotations for variables. This means that a given variable name could refer to values of multiple types over the course of execution of the program.

def guess_my_number(secret_value):

val = get_number_from_user()

if val > 100:

val = "Your guess is too large!"

else:

...

How does a program written in a dynamically typed language detect type violations? Usually the compiler/interpreter would use a type tag, an extra piece of data stored along with each value that indicates the type of the value.

def add(x,y):

print(x + y)

def foo():

a = 10

b = "cooties"

add(a, b)

So in this example, the compiler would store the fact that the value a is pointing to is an int with value 10, and b is a string with value cooties.

Sometimes statically typed languages also need to perform run time type checks. This is most often seen during down-casting (when casting an object from a child class to a parent class). Consider the following example.

class Person { ... };

class Student : public Person { ... };

class Doctor : public Person { ... };

void partay(Person *p) {

Student *s = dynamic_cast<Student *>(p);

if (s != nullptr)

s->getDrunkAtParty();

}

int main() {

Doctor *d = new Doctor("Dr. Fauci");

partay(d);

delete d;

}

dynamic_cast does a run time check to ensure that the type conversion (from Person* to Student*) we are performing is valid. If it isn’t valid, dynamic_cast will return nullptr.

In strongly typed languages, variants would also require dynamic type checking.

Pros of dynamic type checking

- Increased flexibility

- Often easier to implement generics that operate on many different types of data

- Simpler code due to fewer type annotations

- Makes for faster prototyping

Cons of dynamic type checking

- We detect errors much later

- Code is slower due to run time type checking

- Requires more testing for the same level of assurance

- No way to guarantee safety across all possible executions (unlike static type checking)

Duck typing

Duck typing emerges as a consequence of dynamic typing. With static typing, we determine the what operations work on a particular value/variable based on the type of the value/variable. But a consequence of dynamic typing is that variables no longer have a fixed type. This means that we can pass a value of any type to a function, and as long as the type of the value implements all of the operations used in the function, the code should work fine.

Consider the following example.

# Python "duck" typing

class Duck:

def swim(self):

print("Paddle paddle paddle")

class OlympicSwimmer:

def swim(self):

print("Back stroke back stroke")

class Professor:

def profess(self):

print("Blah blah blah blah blah")

def process(x):

x.swim()

def main():

d = Duck()

s = OlympicSwimmer()

p = Professor()

process(d) # Paddle paddle paddle

process(s) # Back stroke back stroke

process(p) # throws AttributeError

Since Duck and OlympicSwimmer both implement the swim method, the code works. When it gets to Professor, which doesn’t implement swim, that’s when you get the error.

The values you pass to process only need to implement swim, they do not have to be related to each other. Duck typing has some interesting applications.

Supporting enumeration

In Python, you can make any class iterable by just implementing the __iter__ and __next__ methods.

# Python duck typing for iteration

class Cubes:

def __init__(self, lower, upper):

self.upper = upper

self.n = lower

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.n < self.upper:

s = self.n ** 3

self.n += 1

return s

else:

raise StopIteration

for i in Cubes(1, 4):

print(i) # prints 1, 8, 27

Making any class printable

In Python, you can make any class printable (using print) by just implementing the __str__ function

# Python duck typing for printing objects

class Duck:

def __init__(self, name, feathers):

self.name = name

self.feathers = feathers

def __str__(self):

return self.name + " with " + \

str(self.feathers) + " feathers."

d = Duck("Daffy", 3)

print(d)

Testing for equality

In Python, if you add the __eq__ method to any class, you can make it’s objects “comparable”.

# Python duck typing for equality

class Duck:

def __init__(self, name, feathers):

self.name = name

self.feathers = feathers

def __eq__(self, other):

return (

self.name == other.name and

self.feathers == other.feathers

)

duck1 = Duck("Carey",19)

duck2 = Duck("Carey",19)

if duck1 == duck2:

print("Those are the same duck!")

Other dynamically typed languages also offer duck typing!

Ruby

# ruby duck typing

class Duck

def quack

puts "Quack, quack"

end

end

class Dog

def quack

puts "Woof... I mean quack!"

end

end

animals = [Duck.new,Dog.new]

animals.each do |animal|

animal.quack()

end

JavaScript

// JavaScript duck typing

var cyrile_the_duck = {

swim: function ()

{ console.log("Paddle paddle!"); },

color: "brown"

};

var michael_phelps = {

swim: function ()

{ console.log("Back stroke!"); },

outfit: "Speedos"

};

function process(who) {

who.swim();

}

process(cyrile_the_duck); // Paddle paddle!

process(michael_phelps); // Back stroke!

It is possible to have something similar to duck typing in statically typed languages (like C++) as well. In C++, this is done using templates.