Lecture 07

2023-04-24 | Week 4 | edited by Matt Wang

(originally written 2022-10-17 by Siddarth Krishnamoorthy)

Matt here! After hearing from Brian Kernighan (which was awesome!), we covered slides 16-52 of Data Palooza.

Table of Contents

Types

In this section, we will take a deep dive into typing and type checking. You should hopefully get a much better idea of the implications of a type system.

Before proceeding, it’s worth asking if are types even necessary to create a programming language?

Yes! It is possible to have a language with no types. Assembly languages are one such example of languages with no type system. They just have a register that holds a 32 (or 64) bit value. The value could represent anything (an integer, float, pointer, etc.). BLISS is another example of a language with no types.

MODULE E1 (MAIN = CTRL) =

BEGIN

FORWARD ROUTINE

CTRL,

STEP;

ROUTINE CTRL =

BEGIN

EXTERNAL ROUTINE

GETNUM, ! Input a number from terminal

PUTNUM; ! Output a number to terminal

LOCAL

X, ! Storage for input value

Y; ! Storage for output value

GETNUM(X);

Y = STEP(.X);

PUTNUM(.Y)

END;

ROUTINE STEP(A) =

(.A+1);

END

ELUDOM

But virtually all modern languages have a type system, since it makes programming so much easier and safer.

Must every variable have a type in a typed language?

No! In Python for example, variables are not associated with types.

# Python

def foo(q):

if q:

x = "What's my type?" # string

...

x = 10 # int

In general, many dynamically typed (don’t worry, we will cover them in this lecture) languages don’t associate variables with types. However, note that a value is always associated with a type.

Types can broadly be classified into two categories, primitive and composite. Primitive data types are a set of types from which other types are constructed. Composite data types are those types which can be constructed using primitive and composite data types.

Examples of primitive data types:

- Integers

- Booleans

- Characters

- Enumerated types (Enums)

- Floats

- Pointers

Examples of derived data types:

- Arrays

- Structs

- Variants/Unions

- Objects

- Tuples

- Containers

There can also be data types that don’t fall into either category.

- Functions

- Generic types

- Boxed types

A boxed type is just an object whose only data member is a primitive (like an int or a float)

class Integer {

public:

int get() const { return val_; }

private:

int val_;

};

In languages like Python that pass by object reference, this lets you “change” a primitive type’s value!

Type checking

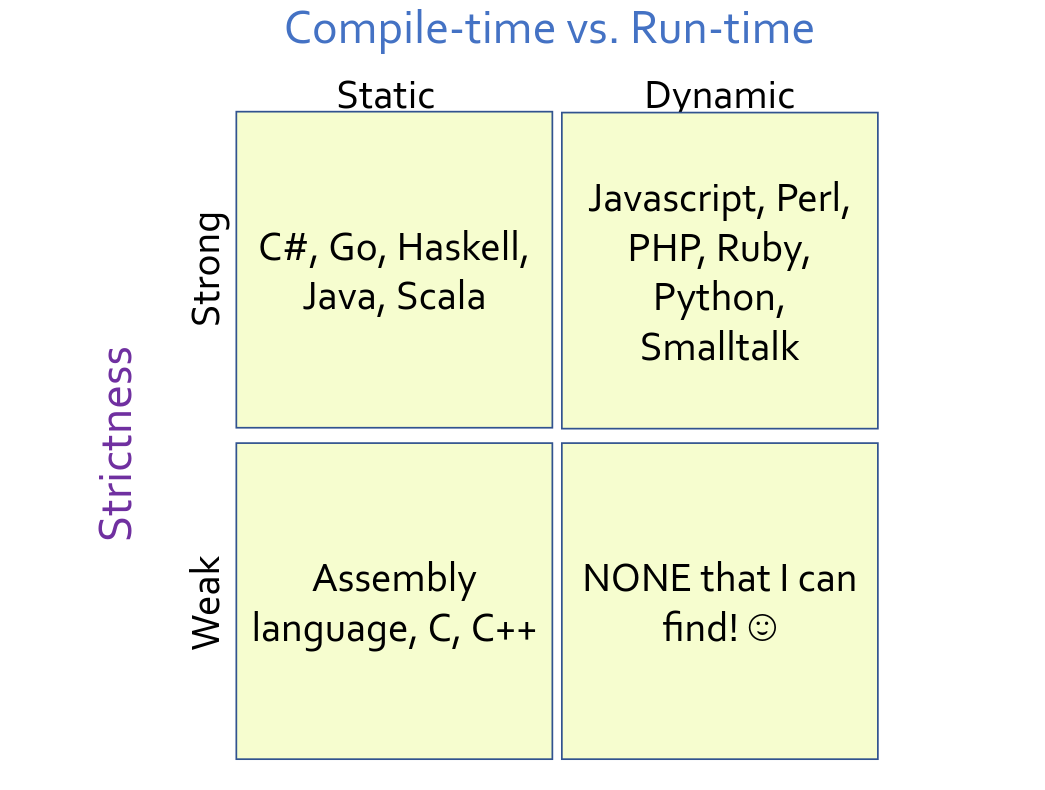

Type checking is the process of verifying and enforcing constriants on types. Type checking can occur during compile time (static) or during run time (dynamic). The language can also specify the degree of strictness for type checking (strong and weak type checking). We will go into more detail on all of these topics.

|

|---|

| Type checking approaches. Type checkers can be classified on the basis of whether they run during compile time or during run time. Type checkers can also be classified on the basis of strictness (strong or weak). |

Static typing

Static typing is the process of verifying that all operations in a program are consistent with the types of the operands prior to program execution. Types can either be explicitly specified (like in C++) or can be inferred from code (like in Haskell). For inferred types, if the type checker cannot assign distinct types to all variables, functions, and expressions or cannot verify type safety, then it generates an error. But if a program type checks, then it means the code is (largely) type safe, and few if any run time checks need to be performed.

To support static typing, a language must have a fixed type bound to each variable at the time of definition.

Type Inference

Type inference refers to the automatic detection of types of expressions or variables in a language. Consider the following example:

void foo(_____ x, _____ y) {

cout << x + 10;

cout << y + " is a string!";

}

What would be the types of x and y? int and string, right! The compiler can infer that y is an string from the fact that we perform the operation y + " is a string", which is only valid if y is a string. What about x? It seems like x can only be an int. But consider this example:

void foo(_____ x, _____ y) {

cout << x + 10;

cout << y + " is a string!";

}

void bar() {

double d = 3.14;

foo(d,"barf");

}

Here, it makes more sense for x to be a double. So type inference is actually a complex constraint satisfaction problem.

A fun observation from Matt - because C and C++ allow pointer arithmetic, in theory x could also be a pointer. Wonky!

Many statically typed languages now offer some form of type inference. C++ has the auto keyword:

// C++ type inference with auto

int main() {

auto x = 3.14159; // x is of type int

vector<int> v;

...

for (auto item: v) { // item is of type int

cout << item << endl;

}

auto it = v.begin(); // it is of type vector<int>::iterator

while(it != v.end()) {

cout << *it << endl;

++it;

}

}

Type inference has limitations! Most languages (like C++, Java, or Rust) will struggle with generic types and iterators; you’ll be forced to write type annotations in some areas.

Go similarly infers the type of variables from the right-hand-side expression

// GoLang type inference

func main() {

msg := "I like languages"; // string

n := 5 // int

for i := n; i > 0; i-- {

fmt.Println(msg);

}

}

Conservatism

Static type checking is inherently conservative. This means that the static type checker will disallow perfectly valid programs that never violate typing rules.

This is due to the fact that for Turing-complete languages, it is not possible to have a sound (meaning all incorrect programs are rejected), decidable (meaning that it is possible to write an algorithm that determines whether a program is well-typed), and complete (meaning no correct programs are rejected) type system. This follows from Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. (Don’t worry if you don’t understand this, it won’t be on the exam :))

For an example, consider the following program:

class Mammal {

public:

virtual void makeNoise() { cout << "Breathe\n"; }

};

class Dog: public Mammal {

public:

void makeNoise() override { cout << "Ruff\n"; }

void bite() { cout << "Chomp\n"; }

};

class Cat: public Mammal {

public:

void makeNoise() override { cout << "Meow!\n"; }

void scratch() { cout << "Scrape!\n"; }

};

void handlePet(Mammal& m, bool bite, bool scratch) {

m.makeNoise();

if (bite)

m.bite();

if (scratch)

m.scratch();

}

int main() {

Dog spot;

Cat meowmer;

handlePet(spot, true, false);

handlePet(meowmer, false, true);

}

The compiler generates an error during the compilation of this code

error: no member named 'scratch' in 'Mammal'

even though the code only asks Dogs to bite and Cats to scratch.

Pros of static type checking:

- Produces faster code (since we don’t have to type check during run time)

- Allows for earlier bug detection (at compile time)

- No need to write custom type checks

Cons of static type checking:

- Static typing is conservative and may error our perfectly valid code

- It requires a type checking phase before execution, which can be slow

Dynamic typing

Dynamic type checking is the process of verifying the type safety of a program at run time. If the code is attempting an illegal operation on a variable’s value, an exception is generated and the program crashes. Here are some examples of dynamic type checking at run time.

def add(x,y):

print(x + y)

def foo():

a = 10

b = "cooties"

add(a,b)

outputs

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

def do_something(x):

x.quack()

def main():

a = Lion("Leo")

do_something(a)

outputs

AttributeError: 'Lion' object has no attribute 'quack'

Most dynamically typed languages don’t require explicit type annotations for variables. This means that a given variable name could refer to values of multiple types over the course of execution of the program.

def guess_my_number(secret_value):

val = get_number_from_user()

if val > 100:

val = "Your guess is too large!"

else:

...

Type Tags

How does a program written in a dynamically typed language detect type violations?

Well, in dynamically typed languages, types are associated with values – not variables! In other words, variables do not have types in dynamically typed languages.

Usually the compiler/interpreter would use a type tag, an extra piece of data stored along with each value that indicates the type of the value.

def add(x,y):

print(x + y)

def foo():

a = 10

b = "cooties"

add(a, b)

So in this example, the compiler would store the fact that the value a is pointing to is an int with value 10, and b is a string with value cooties.

Sometimes statically typed languages also need to perform run time type checks. This is most often seen during down-casting (when casting an object from a child class to a parent class). Consider the following example.

class Person { ... };

class Student : public Person { ... };

class Doctor : public Person { ... };

void partay(Person *p) {

Student *s = dynamic_cast<Student *>(p);

if (s != nullptr)

s->getDrunkAtParty();

}

int main() {

Doctor *d = new Doctor("Dr. Fauci");

partay(d);

delete d;

}

dynamic_cast does a run time check to ensure that the type conversion (from Person* to Student*) we are performing is valid. If it isn’t valid, dynamic_cast will return nullptr.

Pros of dynamic type checking:

- Increased flexibility

- Often easier to implement generics that operate on many different types of data

- Simpler code due to fewer type annotations

- Makes for faster prototyping

Cons of dynamic type checking:

- We detect errors much later

- Code is slower due to run time type checking

- Requires more testing for the same level of assurance

- No way to guarantee safety across all possible executions (unlike static type checking)

Addendum: Dynamic Type Checking in Statically-Typed Languages

Sometimes, dynamic type checking is needed in statically-typed languages:

- when downcasting (in C++)

- when disambiguating variants (think Haskell!)

- (depending on the implementation) potentially in runtime generics

Duck Typing

Duck typing emerges as a consequence of dynamic typing. With static typing, we determine the what operations work on a particular value/variable based on the type of the value/variable. But a consequence of dynamic typing is that variables no longer have a fixed type. This means that we can pass a value of any type to a function, and as long as the type of the value implements all of the operations used in the function, the code should work fine.

Consider the following example:

# Python "duck" typing

class Duck:

def swim(self):

print("Paddle paddle paddle")

class OlympicSwimmer:

def swim(self):

print("Back stroke back stroke")

class Professor:

def profess(self):

print("Blah blah blah blah blah")

def process(x):

x.swim()

def main():

d = Duck()

s = OlympicSwimmer()

p = Professor()

process(d) # Paddle paddle paddle

process(s) # Back stroke back stroke

process(p) # throws AttributeError

Since Duck and OlympicSwimmer both implement the swim method, the code works. When it gets to Professor, which doesn’t implement swim, that’s when you get the error.

The values you pass to process only need to implement swim, they do not have to be related to each other. Duck typing has some interesting applications.

Supporting enumeration

In Python, you can make any class iterable by just implementing the __iter__ and __next__ methods.

# Python duck typing for iteration

class Cubes:

def __init__(self, lower, upper):

self.upper = upper

self.n = lower

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.n < self.upper:

s = self.n ** 3

self.n += 1

return s

else:

raise StopIteration

for i in Cubes(1, 4):

print(i) # prints 1, 8, 27

Make any class printable!

In Python, you can make any class printable (using print) by just implementing the __str__ function

# Python duck typing for printing objects

class Duck:

def __init__(self, name, feathers):

self.name = name

self.feathers = feathers

def __str__(self):

return self.name + " with " + \

str(self.feathers) + " feathers."

d = Duck("Daffy", 3)

print(d)

Make any class comparalbe!

In Python, if you add the __eq__ method to any class, you can make it’s objects “comparable”.

# Python duck typing for equality

class Duck:

def __init__(self, name, feathers):

self.name = name

self.feathers = feathers

def __eq__(self, other):

return (

self.name == other.name and

self.feathers == other.feathers

)

duck1 = Duck("Carey", 19)

duck2 = Duck("Carey", 19)

if duck1 == duck2:

print("Same!")

Other dynamically typed languages also offer duck typing!

Ruby:

# ruby duck typing

class Duck

def quack

puts "Quack, quack"

end

end

class Dog

def quack

puts "Woof... I mean quack!"

end

end

animals = [Duck.new,Dog.new]

animals.each do |animal|

animal.quack()

end

JavaScript:

// JavaScript duck typing

var cyrile_the_duck = {

swim: function ()

{ console.log("Paddle paddle!"); },

color: "brown"

};

var michael_phelps = {

swim: function ()

{ console.log("Back stroke!"); },

outfit: "Speedos"

};

function process(who) {

who.swim();

}

process(cyrile_the_duck); // Paddle paddle!

process(michael_phelps); // Back stroke!

It is possible to have something similar to duck typing in statically typed languages (like C++) as well. In C++, this is done using templates; there’s also runtime generics in Java, Rust’s generics system, etc.

Gradual Typing

Gradual typing is a hybrid approach between static and dynamic typing. It’s used by a few well known languages like PHP and TypeScript, so it merits discussion.

In gradual typing, some variables may have explicitly annotated types, while others may not. This allows the type checker to partially verify type safety prior to execution, and perform the rest of the checks during run time.

With gradual typing, you can choose whether to specify a type for variables/parameters. If a variable is untyped, then type errors for that variable are detected at run time. But if a variable is typed, then it’s possible to detect some type errors at compile time. But what if we pass an untyped variable as an argument to a typed variable? Look at the following code snipped for a concrete example.

def square(x: int):

return x * x

def what_happens(y):

print(square(y))

This is actually allowed in gradually typed languages! If you pass an untyped variable as an argument to what_happens, the type checker will check for errors during run time. This way, if you do use an invalid type, the program will generate an error the moment an incompatible type is detected.

Let’s try and classify a language.

fun greet(name: String) {

print("Hello, $name!")

}

fun main() {

var n = "Graciela";

greet(n);

n = 10;

}

Is this language dynamically, statically or gradually typed, given that the code generates the following error?

The integer literal does not conform to the expected type String

Answer: Even though it doesn’t look like it at first glance, the language is statically typed, since you can’t assign n to a value of a new type. This means that n has a fixed type, and that the language is using type inference. This language is actually Kotlin!

Strong typing

Now that we have a good idea of static and dynamic typing, we’re going to look at the various type checking approaches on the basis of strictness. A strongly typed language ensures that we will never have undefined behaviour at run time due to type issues. This means that in a strongly typed language, there is no possibility of an unchecked run time type error.

The definition of strong typing is disputed. Many academics argue for a stronger definition (e.g. all conversions between types should be explicit, the language should have explicit type annotations for all variables, etc.). But ultimately while these definitions may make a languages type system stricter, they don’t impact the languages type or memory safety.

These are the minimum requirements for a language to be strongly typed:

- the language is type-safe: the language will prevent an operation on a variable

xifxs type doesn’t support that operation.int x; Dog d; a = 5 * d; // Prevented - the language is memory safe: the language prevents inappropriate memory accesses (e.g., out-of-bounds array accesses, accessing a dangling pointer)

int arr[5], *ptr; cout << arr[10]; // Prevented cout << *ptr; // Prevented

These can be enforced either statically or dynamically!

Languages usually use a few techniques to implement strong typing:

- before an expression is evaluated, the compiler/interpreter validates that all of the operands used in the expression have compatible types.

- all conversions between different types are checked and if the types are incompatible (e.g., converting an int to a Dog), then an exception will be generated.

- pointers are either set to null or assigned to point at a valid object at creation.

- accesses to arrays are bounds checked; pointer arithmetic is bounds-checked.

- the language ensures objects can’t be used after they are destroyed.

In general, strongly typed languages prevent operations on incompatible types or invalid memory.

Why do we need memory safety?

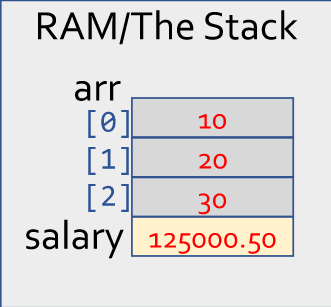

Why do strongly typed langauges require memory safety? To answer this question, consider the following example in C++ (a weakly typed language).

// C++

int arr[3] = {10, 20, 30};

float salary = 120000.50;

cout << arr[3]; // out-of-bounds access

arr[3] actually access the value stored in salary, since all local variables are stored on the stack. So if a language is not memory safe, then it’s possible to access a value (like salary) using an invalid type (int instead of float). Accessing a dangling pointer is another example of how memory safety can violate type safety.

|

|---|

In C++, arr[3] would actually access the value stored in salary as if it were an integer! |

// Accessing a dangling pointer

float *ptr = new float[100];

delete [] ptr;

cout << *ptr; // is this still a float?

Checked type casts

A checked cast is a type cast that results in an exception/error if the conversion is illegal. Let’s look at a concrete example in Java, a strongly typed language. Consider the following snippet of code.

public void petAnimal(Animal a) {

a.pet(); // Pet the animal

Dog d = (Dog)a; // Probably a dog, right?

d.wagTail(); // It'll wag its tail!

}

...

public void takeCareOfCats() {

Cat c = new Cat("Meowmer");

petAnimal(c);

}

In this case, the program would output a type error saying that Cat can’t be type cast to Dog.

java.lang.ClassCastException: class Cat cannot be cast to class Dog

A similar snippet of code in C++ however would run, even though we are dealing with an object of type Cat, not Dog!

void petAnimal(Animal *a) {

a->pet(); // Pet the animal

Dog* d = (Dog *)a;

d->wagTail();

}

...

void takeCareOfCats() {

Cat c("Meowmer");

petAnimal(&c);

}

When the C++ program actually executes d->wagTail(), anything could happen. This is undefined behaviour (we will cover undefined behaviour later in this lecture).

Why should we prefer strongly typed languages? Well, they have two main benefits.

- They dramatically reduce software vulnerabilities (e.g. buffer overflows).

- They allow for early detection and fixing of errors/bugs.