Lecture 01

2023-04-03 | Week 1 | edited by Matt Wang

(originally written 2022-09-26 by Matt Wang)

Heya! Matt here. This lecture note covers the intro slide deck up to slide 47. If you have feedback on how this is done, please let me know!

Table of Contents

Logistics

tl;dr: please read the syllabus and check out the core resources, including:

- the course calendar, which has every homework, project, and lecture

- the weekly schedule, which has class and discussion timings and office hours

- the staff list, with contact info for Carey + TAs

- the CampusWire, where we answer questions!

Unfortunately, no extra enrollment (PTEs, waitlists) can be accomodated at this time. In particular, we are not auto-enrolling people off the waitlist.

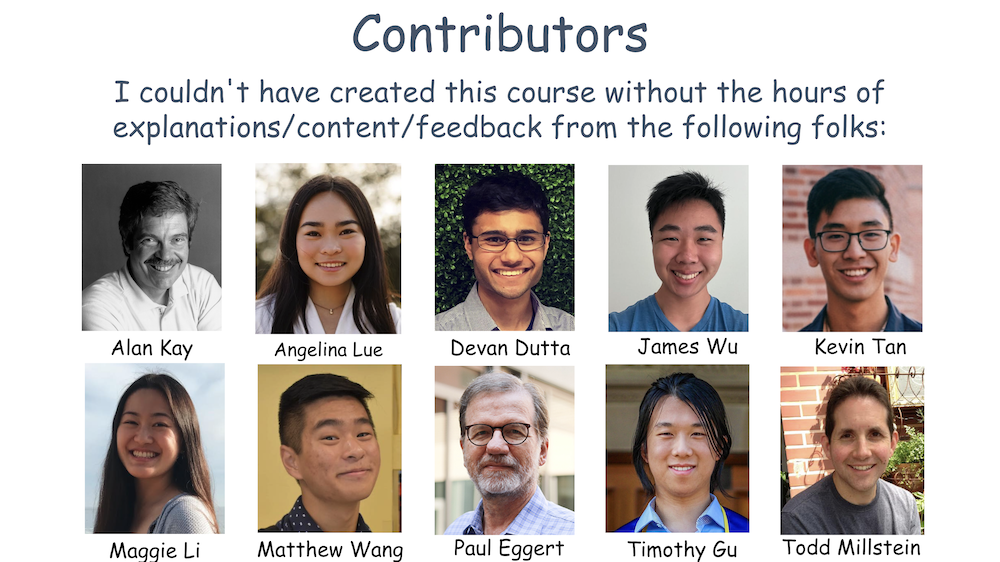

The slides also have shoutouts for many people who helped out!

What is CS 131?

The goal of 131 is not to teach you every programming language! Instead, we want to understand the core paradigms and building blocks that go into languages, and the tradeoffs that languages make. Then, you can pick up new languages super quickly (which … you’ll do all the time as a software engineer)!

Some examples of paradigms and building blocks:

- functional programming

- object-oriented programming

- type systems

- memory management

- and many, many, many, more!

Practically, we’ll be focusing heavily on Python - you’ll write thousands of lines of code in it! In contrast, we’ll also gain basic proficiency in Haskell and Prolog.

Along the way, we’ll learn tiny tidbits of these paradigms and building blocks in other languages - like Rust, Go, Scala, and of course, C and C++!

To test your knowledge, we’ll have:

- a project (split into 3 parts) where you build your own interpreter for a custom language!

- 9 homeworks, which are graded on effort only

- a midterm and a final exam!

- the midterm is on Thursday, May 4th from 6PM - 8PM, which is not during class!

There is no textbook for the class (the slides + notes will be that resource). Be careful with using online resources - terminology differences mean that sites like StackOverflow can be incorrect! Carey recommends some resources:

- language comparisons: Rosetta Code and Hyperpolyglot

- gentle Haskell introduction: Learn You a Haskell

- gentle Prolog introduction: Tutorialspoint

A note for note takers - be careful writing super detailed notes, since you might not be able to keep up with code examples. So, don’t write all the code down; instead, engage with the content in class!

Programming Languages

What is a programming language? Carey’s definition:

A programming language is a structured system of communication designed to express computations in an abstract manner.

There are many other definitions, but we like this one! Our focus is going to be on “high-level” programming languages, which are generally human-readable and implement most languages we care about :)

There’s some wonderful history about programming languages - including Grace Hopper’s pioneering work in creating the first compilers (for A-0) and the first human-readable language (COBOL) - I would recommend reading more about Grace Hopper (or coming to my discussion!).

Why Variety?

As you’re probably aware, there are many, many programming languages (thousands!). At the end of the quarter, we’ll make an interpreter for our very own.

But, why? Well, different languages tend to be good at different things. Some programming languages are better suited towards solving different problems. Some languages are Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs) that solve very specific problems (like laying out circuit boards).

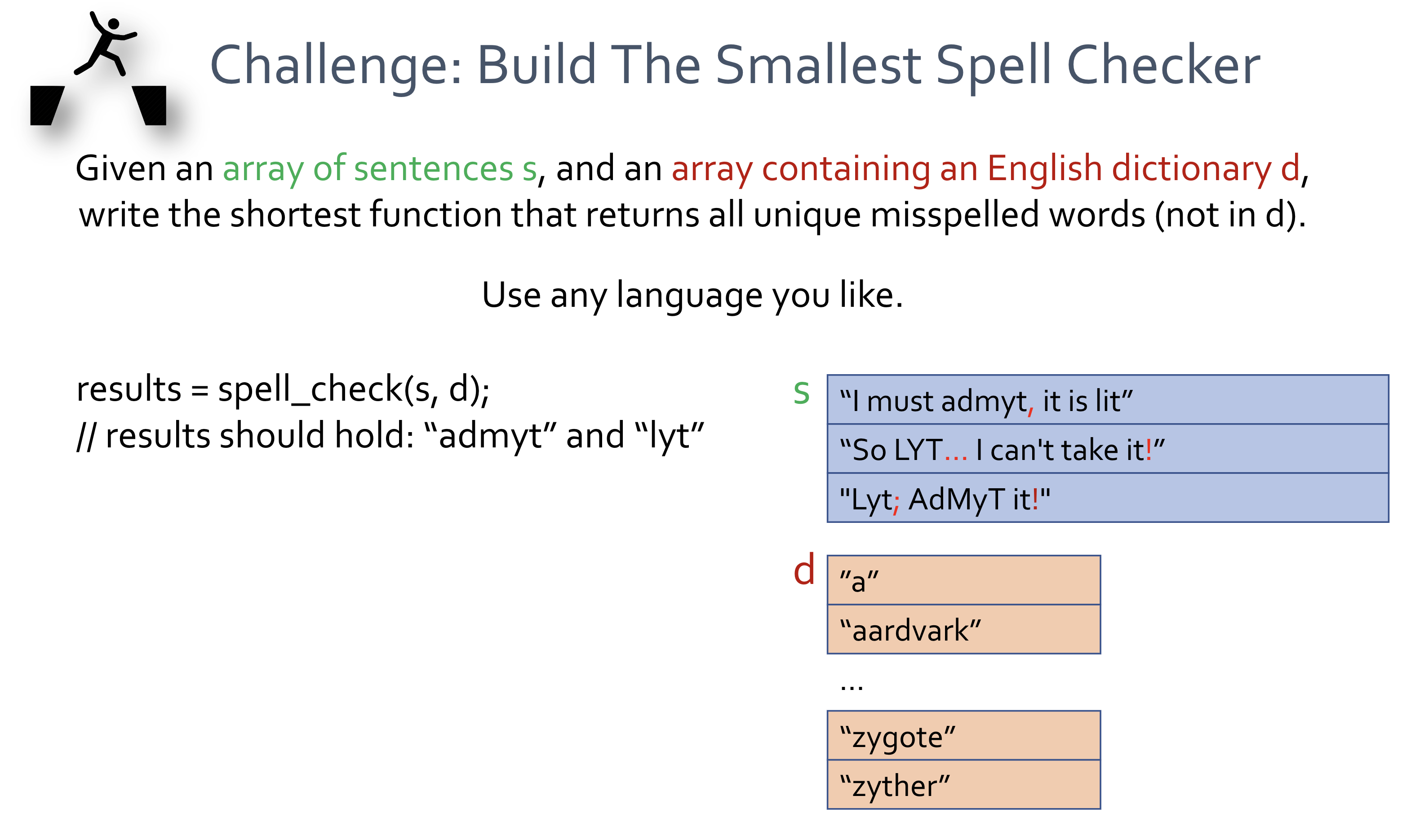

In class, we went through taking on a creating a spell checker.

Even though this sounds complicated, we can implement a simple solution in Python:

import re

def spell_check(s, d):

return {w for w in [w for ln in s for w in re.split(r'[. ,!;"]',ln)]

if w.lower() not in d and w != ''}

This is pretty concise for a seemingly-hard problem! Part of this comes from Python’s design decisions - a powerful standard library and functional features like list comprehensions!

(in other languages, like Java, the solution is probably more verbose!)

Paradigms

Programming languages (like Starbucks drinks?) have key paradigms, which define the core of a language. Let’s quickly talk about four major paradigms.

Imperative languages are all about statements. Programs are one statement after another; you can use loops to control statements, change variable values, etc. You have used many imperative languages!

Here’s a loop in C that exhibits imperative properties:

int a = 0;

while (a++ < 100)

cout << a << endl;

Object-oriented languages are all about objects. Programs are organized into classes and objects which send messages (i.e. method calls) to each other. You’ve used several of these too!

Modern OOP syntax derives heavily from Smalltalk:

class Dog { ... };

Functional languages are all about functions. Programs are just compositions of math-like functions (expressions!). Importantly, there are no statements or iteration - the bread and butter of functional programming is recursion!

We’ll learn Haskell this quarter:

f(n) = if n > 0 then n * f(n - 1) else 1

Logic languages are all about facts. You can define rules about facts, and query your existing facts. Logic languages are uncommon, but a whole new approach to problem solving!

Here’s a Prolog example:

like(dogs, meat), category(beef, meat)

likes(A,C): if like(A,B) and category(C, B)

likes(dogs, beef)?

Many languages mix paradigms!

- C++ is imperative and object-oriented (with … some functional elements)

- Scala is object-oriented and functional

You might ask - I haven’t used Functional or Logic languages. Why are we learning these?

- functional programming is common in almost every modern language - from JS and Python to C++ and Java!

- while you won’t use logic programming in your job (probably?), it teaches you a whole new way of thinking :)

- and, lots of problems are best solved with multiple paradigms - the more tools in your toolkit, the better!

Building Blocks and Dimensions

Beyond these paradigms, there are many other dimensions that separate programming languages. Just like Starbucks drinks – where you can pick the milk, syrup, or sweetener – you can customize programming languages in their:

- type systems: static versus dynamic

- parameter passing: by value, reference, pointer, object reference, name

- scoping: lexical versus dynamic

- memory management: manual versus automatic

- and more!

Each language - like C++ or Python - makes (different) decisions in what to do. In turn, this affects the behaviour of the language, and what kinds of problems they solve!

There are some dimensions with bite-sized scopes and pro-cons.

Variable assignment: can you declare before assignment?

- choice: how verbose do you want your code to be?

- choice: when do you want to detect errors (runtime versus compile time)

Implicit type conversions: should the programming language convert types for you?

- choice: how simple do you want your code to be?

- choice: what bugs are you okay with?

Array bounds checks: should the language check if an array index is in-bounds?

- choice: performance!

- choice: nasty memory bugs :(

Exercise: Classify that Language

(this is one of Matt’s favourite parts of this class!!)

Let’s sketch out our approach to learning more about languages. Let’s look at this language that we’ve totally never seen before:

class Student:

... # details hidden

# student goes through life changes

def life_changes(s: Student):

s.change_major("Econ")

# hates life choices, so starts from scratch

s = Student("Carence", "Music")

# main program

student1 = Student("Carey", "CompSci")

life_changes(student1)

student1.print_my_details();

When we run the program, it prints Carey's major is Econ..

The big question: How does this language pass parameters?

- By value?

- By reference?

- By pointer?

Let’s do some sleuthing!!

- It printed Econ. So,

s.change_majordoes actually change thesvalue. In particular, it’s not passing by value - that creates a copy! - It printed Carey. So, the last assignment in

life_changes-s = Student(...)- didn’t change the origianl object! In particular, that meanssis a pointer, not a reference! - So, it’s passing by pointer! (okay, in Python - the language, this is called passing by object reference, but we were pretty close); the slides have a neat animation that explain this more

If this language passed by value, this would print Carey's major is CompSci. since all the changes in life_changes only affect the copy. If this language passed by reference, this would print Carence's major is Music. since all of the changes would be reflected in the reference.

We’ll do more of these every week! And, by the end of the quarter, you’ll be able to do this on your own - every time you see a new language!

Specifying a Language?

How would we specify the details of a programming language? While there are many ways, they broadly fall into two categories:

- syntax: what legal combinations of strings are allowed to be typed into a program? (like a grammar!)

- semantics: what is the meaning of each string? what does the program actually do? this includes many things: type checking, operators, parameter passing, …

Interestingly, there are many ways to specify semantics - in written English (like in C++), “formal mathematics” (like ML), or … none (Perl)!

Note: whether or not a language is compiled or interpreted is not a feature of a language! For example, there are compiled versions of Python :)

Language Tooling

This section will not be on the exam! It’s just for your education. It is super relevant in all software engineering!

There are a lot of tools that go into programming languages; here’s a quick flyover:

- a compiler is a program that translates program source code into object modules (machine language or bytecode)

- an alternative view: a compiler translates a program from one language to another, but doesn’t run it

- a linker is a program that combines multiple object modules and libraries into a single file

- an interpreter is a program that directly executes program statements, without requiring them to be compiled!

Compilers

A compiler has a workflow that:

- starts with a source file

- a lexical analyzer converts the source file into a stream of tokens or lexical units - think

whileor( - a parser checks if the tokens have valid syntax (using the language’s grammar!)

- if the syntax is valid, the parser converts the tokens to an abstract syntax tree, which organizes the tokens in a tree format

- the semantic analyzer checks if the tree has valid semantics and annotates the tree with some extra info (like types), creating an annotated parse tree

- an intermediate representation (IR) generator converts an annotated parse tree to a “generic” assembly language (intermediate representation); this is independent of the original language

- finally, a code generator converts the IR code into machine code or bytecode, which runs on your machine (and depends on your architecture)

- bytecode is a binary encoding, but not for a real CPU; instead, it’s processed by an interpreter or just-in-time compiler

- in a way, this is a “fake” assembly language

The first compiler (for Fortran) was written in assembly language. But… what language are most C++ compilers written in?

C++!

Wait, what? How would that work? Through bootstrapping:

- first, write a C++ translator (~compiler) in some other language that you can run (like C)

- then, write a C++ compiler in C++ (even though you don’t have a working compiler!)

- finally, run that first C++ compiler through your C++ translator to get a C program

- compile it with your C compiler - now you have a runnable C++ compiler!

- finally, using your runnable C++ compiler, recompile your C++ compiler itself - and now, you’re done :)

Why would you bootstrap?

- you don’t depend on any other language (what if it gets deprecated, makes a change you don’t like, etc.)

- sometimes, it’s faster :)

Interpreters

Quickly recall what we said about interpreters:

An interpreter is a program that directly executes program statements, without requiring them to be compiled!

Its workflow looks like:

- load the source file into RAM

- initialize the state (data structures) needed by the interpreter - like the next line we want to run, or if we should exit

- then, run an “infinite” while loop:

- if the program should stop running, exit the loop (and interpreter)

- otherwise, fetch the next statement to run

- interpret the statement and update state

- set the new “next” statement

Carey promises it’s not that complicated! Let’s write one - in one page (or slide).

Consider a toy language with four keywords:

set variable valuesetsvariabletovalueadd variable valueaddsvaluetovariable(think of+=)print variableprints the value stored invariableendterminates the program

Here’s a small program that demonstrates all the items (and prints 30):

set v1 10

add v1 20

print v1

end

Now, our interpreter! First, let’s spin up how we’d use it:

int main() {

vector<string> program = {"set v1 10",

"add v1 20",

"print v1",

"end"};

Interpreter inter(program);

inter.run(); // prints 30

}

And, as promised, the one-page interpreter:

class Interpreter {

public:

Interpreter(const vector<string>& program)

{ program_ = program; }

void run() {

cur_line_ = 0;

terminated_ = false;

while (!terminated_)

execute_statement();

}

private:

void execute_statement();

vector<string> program_;

int cur_line_;

bool terminated_;

map<string, int> variables_;

};

void Interpreter::execute_statement() {

const string& stat = program_[cur_line_];

vector<string> tokens = split(stat,' ');

if (tokens[0] == "end") {

terminated_ = true;

return;

}

if (tokens[0] == "set")

variables_[tokens[1]] = stoi(tokens[2]);

else if (tokens[0] == "add")

variables_[tokens[1]] += stoi(tokens[2]);

else if (tokens[0] == "print")

cout << variables_[tokens[1]] << endl;

++cur_line_;

}

Note how this mirrors the steps we discussed!

- when

.run()is called, we set up the state and then the while loop - when executing each statement, we check:

- have we hit the end token? if so, end

- if not, process the current statement, change the state, and then move on to the next line

Why is this important? Well, in your project, you’ll be doing the same high-level idea - but with more complicated features!